The skilled court jewelers whose creations adorned the fabled Romanovs are the stars of a new book on the royal family’s finery.

Russia’s ruling Romanov family had a passion for jewels, and the upcoming book Beyond Fabergé: Imperial Russian Jewelry focuses on the rarified talents of the creators responsible for these dazzling works. Written by Marie Betteley and David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, it comes out in late October and takes readers behind the scenes of the magnificent gem-laden tiaras, necklaces, ceremonial and decorative objects these monarchs amassed.

Betteley began her love affair with Russian treasures in her teen years, when her father, Roy Betteley, became director of the Hillwood Museum in Washington, DC, and the family moved to the estate. The former home of cereal heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post, Hillwood houses one the largest collections of pre-revolutionary Russian decorative arts in the world.

“I was surrounded by the glories of imperial Russia at an early age,” recalls Betteley, now a dealer. “Then, in my 20s, as a gemologist at Christie’s cataloguing jewels for upcoming sales, I came across a fascinating collection of Russian jewels and fell in love.” It inspired her to find out more about the jewels’ history and who had made them. “That’s when it all started.”

Thanks to a Russian émigré grandfather, co-author Schimmelpenninck van der Oye — who is also Betteley’s husband — shares her fascination with the culture of imperial Russia.

“He’s a specialist on the late imperial period and has helped me throughout my career, as he’s fluent in Russian,” she explains. “Dave’s approach was more historic, whereas mine was market-oriented, as that’s my background.”

Beyond Fabergé not only traces the sweeping history of Russian jewelry over the centuries, but also explores “the roots of Russia’s taste for opulent adornment, as well the intimate relations between imperial jewelers and the court,” says Betteley. “We introduce readers to such leading lights as the House of Bolin, Friedrich Köchli, and Carl Hahn, as well as the Moscow silver masters Pavel Ovchinnikov, Orest Kurliokov and Iosif Marshak of Kiev, to name but a few.”

In keeping with the authors’ respective specialties, the book is divided into two sections: “History” and “Market.”

“The latter…is driven by my own fascination with the subject as a dealer,” Betteley remarks. “I am lucky to have a library filled with Russian auction catalogs dating back 100 years.”

Putting Fabergé in perspective

In the chapter on Fabergé, without which “no book on Russian jewelry is complete,” Betteley notes, “we put the firm in proper perspective by casting it as a shining star rather than the sun in a constellation of master jewelers.” Hence the book’s title.

It’s a tack that might surprise Western readers, she admits. “People don’t realize that long before Fabergé’s tenure, the imperial era marked the high point of the Russian jewelers’ art. By the mid-19th century, the quality of St. Petersburg’s jewelry equaled if not surpassed the best that Paris, London, Rome and Vienna could offer.”

Apart from a focus on Fabergé, she says, “few publications in the West cover the rich history of Russian jewelry. Our book is the first systematic survey of all the leading Russian jewelers and silversmiths in any language.” Most of the information is new, if not groundbreaking, “based on research we conducted over seven years in the Russian archives and [in] published Russian, English, German and French sources.”

The chapter on “The Fate of the Russian Crown Jewels,” she points out, reveals details never before published in English. “What makes it relevant to us as Westerners is that most of the Russian crown jewels were sold to the West and may very well still be here! In this chapter, we trace those items we know were resold, and offer images of those still at large.”

Insiders and innovators

The magnificent jewels of the Romanov rulers helped define their wealth and power to the world. In turn, their passion for acquiring these bejeweled pieces led court jewelers to new heights of creativity.

“Russia’s court was deemed the richest in Europe for a reason,” says Betteley. “Many jewelers, particularly those with the Imperial Warrant — the seal and title granted by the Imperial Cabinet allowing them to show they were suppliers to the tsars — were influenced by the tastes of the Russian monarchs. From 1725, with the rule of Catherine I, to the end of Catherine the Great’s reign in 1796, women ruled Russia, and the production of jewels for the court skyrocketed, keeping scores of jewelers, goldsmiths, silversmiths and luxury-goods makers feverishly busy.”

Of the many jewelers who worked in the country at the time, Betteley highlights “18th-century Swiss immigrant Jeremie Pauzié, who was very close to the court and witnessed five palace coups, and the House of Bolin, which was the best in the 19th century. Pauzié created new techniques of gem-cutting and casting, and was a Renaissance man of the trade. Carl Edvard Bolin outshone all other jewelers with the production of magnificent parures for his aristocratic clients. His revenue was three times that of Fabergé, whose focus was more on objects of vertu, up until the beginning of the 20th century.”

There were other standouts as well. “In enamels, it was Fedor Rückert, and in silver, Sazikov. Founded during the reign of Catherine the Great in Moscow, Sazikov introduced historicism in Russian silver, excelled in the Style Russe and won great acclaim in international exhibitions, particularly in 1851 in London. Decades before Fabergé’s famous guilloché enamels, Sazikov introduced to Russia the tour à guillocher, an engine-turning machine made in France.”

Icons of the monarchy

Using adjectives like “glamorous,” “sensual,” “magnificent” and “innovative” to describe the work of these leading jewelers, Betteley points to the Russian crown jewels as exquisite examples. “We’re lucky because we have a record of the collection before the majority of it was sold to the West. Sometimes I can tell from across an auction viewing room when a jewel is Russian, just by its grand scale.”

The most iconic, she says, are the jewels of the imperial regalia: “Catherine the Great’s diamond crown by Pauzié, dating from 1762; the Orlov scepter; the gold orb; and the magnificent mantel clasp and diamond-encrusted collar of Saint Andrew the First Called — all preserved in the Diamond Fund of the Moscow Kremlin. Symbolizing Romanov rule and power, [these items were] worn for every coronation until the demise of the dynasty in 1917.”

Other notable jewelry worn at court included “lavish parures set with rubies, emeralds, sapphires and diamonds, and diamond rivières, which were de rigueur in imperial Russia. Most were commissioned by the imperial family or aristocracy, particularly for weddings. One example of many is the diamond rivière Hahn created for Grand Duchess Irina, who married Felix Yusupov in 1914. Included in the chapter on Hahn is the original sketch and details from the archives.”

The collector’s market

The book also explores the market for these Russian works, something Betteley knows intimately as a dealer. “Russian gem-set jewelry from before 1917 is very collectible and tends to go for far more than comparable jewels from Europe or America. This is because there are so few examples on the market. I’m always interested in buying mostly from the public, as that’s when you get wonderful, often dramatic family stories. It’s also a good time for collectors to buy Russian jewels, as prices are not as astronomical as they were 10 years ago.”

The book, she comments, is aimed at both serious collectors and people curious about the Romanovs and Russia’s past. “With an extensive glossary of hallmarks, I believe it will also appeal to jewelry professionals, dealers, appraisers, art historians, curators, librarians, bloggers, and lovers of beauty and history around the world.”

Betteley hopes to transmit her own sense of wonder to the readers, offering them “a new understanding of how important Russian jewelry and silver was in the history of the arts.”

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

A third-generation jewelry dealer and graduate gemologist, Marie Betteley began her career at Christie’s in New York, where she rose to head of the Russian department. After 10 years at Christie’s, she launched her own business, opening a gallery in Manhattan specializing in Russian jewels. An authority on imperial Russian decorative arts and jewelry, she consults for auction houses, museums and collectors.

David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye is a professor of Russian history at Brock University in Ontario, and a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. A leading specialist in the imperial era, he is the author of Toward the Rising Sun and Russian Orientalism.

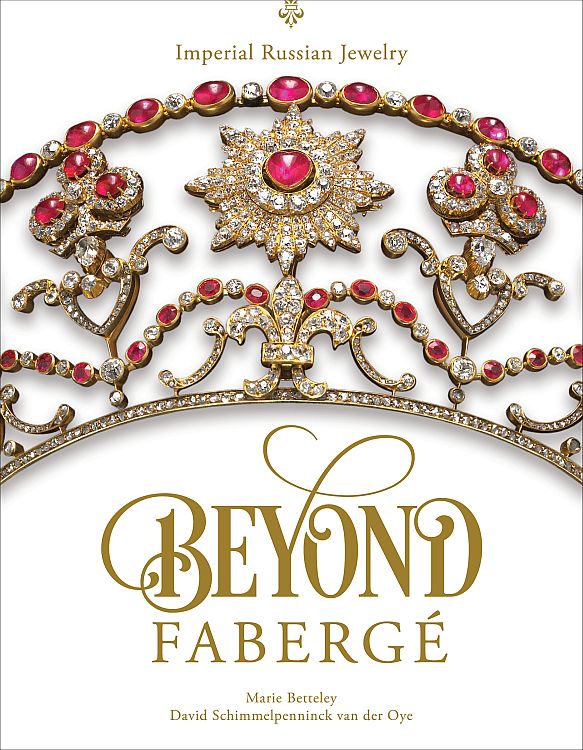

Main image: Russian diamond tiara in the form of a Kokoshnik set with a 13-carat pink diamond from the era of Tsar Paul. Image: Nikolai Rakhmanov.

Comments are closed.