The jewelry that the famed Mexican artist wears in her paintings is a window into her identity, says lecturer Elyse Zorn Karlin.

Mexican painter Frida Kahlo used her life’s experiences as a canvas to create deeply personal paintings that incorporate not only the physical and emotional challenges she endured, but also her feelings of nationalism and feminism.

“In more than 55 self-portraits, Kahlo allows the observer to see what mattered to her,” says Elyse Zorn Karlin, co-director of the Association for the Study of Jewelry and Related Arts (ASJRA). One of the ways that manifests is in the different types of jewelry she painted herself wearing — a subject Karlin addressed this month in her lecture “The Jewelry and Art of Frida Kahlo.” The lecture was part of the annual Jewelry History Series ahead of the Original Miami Beach Antique Show.

Between two worlds

Born in 1907 to a German photographer father who had emigrated to Mexico, and a mother of Spanish and Mexican indigenous descent, Kahlo was the first Mexican artist to have a painting bought by the Louvre museum in Paris. At the time of her death in 1954, she was famous in her home country and had exhibited in New York and in Paris.

Kahlo grew up during the violent upheaval of the Mexican Revolution, which lasted from 1910 to 1920. She contracted polio when she was six, and it left one leg thinner than the other, something she covered up by wearing long skirts. When she was 18, she was in a bus accident that left her severely injured. She couldn’t walk for many months, and it was during this extensive convalescence period that she started painting. As a result of the injuries, Kahlo had to endure several surgeries throughout her life. Along with the lasting pain, she suffered several miscarriages, and she expressed the physical and emotional toll in her paintings.

Although her art has been called surrealistic, Kahlo has stated that “I never paint dreams or nightmares. I paint my own reality.”

In 1929, she married famous Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, 20 years her senior. Their union was tempestuous, with infidelities on both sides — he even had an affair with her sister Cristina, and she with Soviet revolutionary Leon Trotsky. They divorced in 1939, only to remarry the next year.

“She was torn between her European side and her Mexican side,” states Karlin. “She was torn about her sexuality — she painted her distinctive unibrow and slight mustache like badges of honor, emphasizing the male-female dichotomy. Although Kahlo wore traditional Mexican clothes such as the rebozo — a shawl — and the tehuana, a dress with a hood covered in lace, she was also very Bohemian. She went back and forth between being a folk artist and an intellectual.”

In Kahlo’s painting The Two Fridas, which Karlin says shows the push-pull of her dueling sensibilities, Kahlo depicts herself in both traditional Mexican garb and European dress, with the two figures holding hands.

Beads vs. filigree

In many ways, jewelry is a window into who Kahlo was, Karlin continues. “It’s a visible focus; you see it in photographs and her paintings. I started noticing, looking at her paintings, that she wore two distinct kinds of pieces: pre-Columbian beads and carved pieces indigenous to Mexico, and more delicate antique Spanish-Portuguese style jewelry, such as long, dangling earrings.”

Mexico was a colony of Spain for nearly 300 years, Karlin points out, from 1521 through 1821. “Spanish craftsmen came to Mexico, creating jewelry from the gold and silver available using European techniques. One of the important styles was filigree work. This kind of jewelry that wealthy Mexican socialites of Spanish descent would have worn is the type Kahlo illustrates wearing in her paintings.”

That said, Kahlo also wore the heavier, irregularly shaped pre-Columbian beads, usually greenish in color. While jadeite is found in Mexico, they may or may not be jade.

Yet another type of jewelry in the paintings is “pieces with shells and bones,” according to Karlin. “In one picture, she’s wearing earrings that look like little hands hanging down. Those are milagros, small silver objects offered to the saints for protection. Hands were a popular element in milagros.”

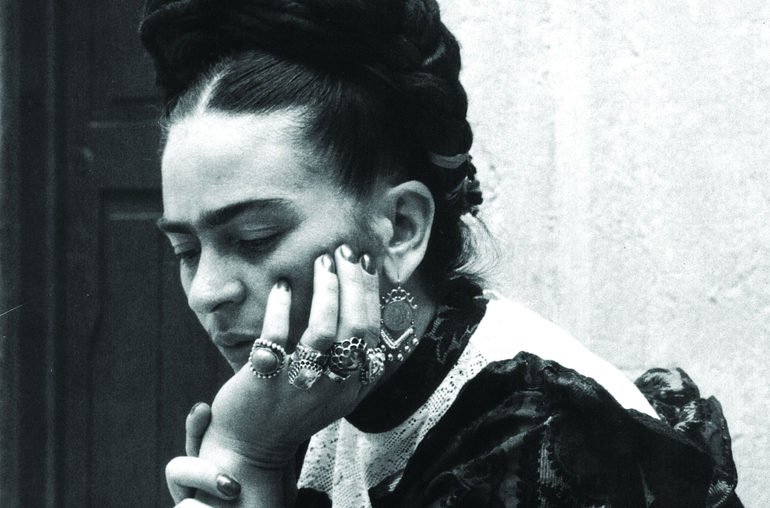

Variations on the theme include European-style jewelry such as hoop earrings, also known as creole earrings, Karlin adds. “Toward the end of her life, Kahlo was bedridden, and there are pictures of her wearing heavy silver rings of the type made in Taxco, Mexico, a town known for its silversmithing and silver mines.”

The ‘Frida craze’

When Kahlo died in 1954 at the age of 47, she “was laid in state, and hundreds of people came,” Karlin relates. Rivera, who died in 1957, said her things had to be packed away and couldn’t be seen until 15 years after his death. In 1958, the house where Kahlo was born and lived — Casa Azul, or the Blue House — became a museum, but her clothing and jewelry remained in storage until 2004.

Kahlo got “rediscovered” in the 1970s “by art historians, political activists and feminists alike, who pointed to the nationalism and feminism in her work,” Karlin comments. “By 1990, there was this ‘Frida craze.’”

And Kahlo’s popularity continues. Her paintings Portrait of a Lady in White (circa 1929) and The Flower Basket (1941) recently sold at Christie’s New York for $5.8 million and $3.1 million, respectively, showing that her work has lasting appeal.

Main image: Frida Kahlo photographed by Lola Alvarez Bravo in 1947. Image: Granger Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Comments are closed.