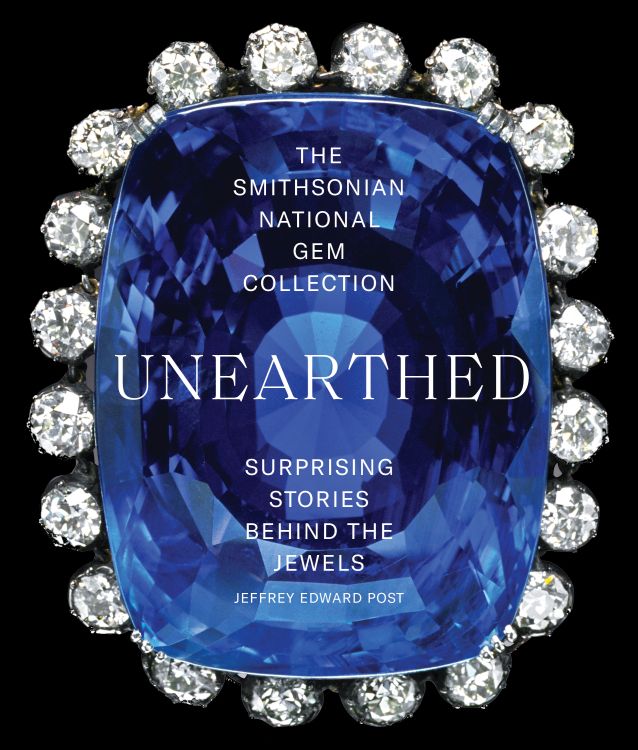

A new book digs deep into the fabulous gems at the Smithsonian Institution.

The mineral and gem collection at the Smithsonian Institution is one of the largest in the world. One of its star attractions is, of course, the Hope Diamond, which millions of visitors a year come to see at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. While the dazzling beauty of the gems on display is what draws people in, the history behind them is equally fascinating, as a new book by the collection’s curator, Dr. Jeffrey Edward Post, illustrates in beautiful detail.

The Smithsonian National Gem Collection — Unearthed: Surprising Stories Behind the Jewels focuses on the backstories of these glorious specimens — not just their historic contexts, but also their former owners. The accounts of how the gems ended up in the museum inevitably intrigue visitors, whether they’re tales of “romance, or power, or war, or enviable wealth,” Post tells Rapaport Magazine.

“Many of the gems are among the finest known and some of the Earth’s great treasures,” he says. “In addition to their beauty and value, they each have a natural-science story and a human story — the people who found and cut them, and the people who owned them and in some cases donated them to our collection.”

In his more than 35 years working with the collection, Post has learned a great deal of this fascinating lore. “In some cases, the previous owners might only be remembered because of their connection to one of our gems. The gems are forever, and therefore, so are their stories.”

A piece of history

Much of the collection’s strength has been due to the donations it has received. The chance to achieve a bit of immortality or create a lasting memorial to a loved one is a strong motivator for these gifts. So is, perhaps, the thought of a timely tax deduction, though in Post’s experience, “most donors are genuinely passionate about gems and are excited to have their stone become part of our National Gem Collection. For some, there is a [sense of] giving back to our nation, and others…want a special gem to be in a place where it can be seen and enjoyed by the public (and studied). When at the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum, the gem can be seen 363 days per year, free of charge, by anyone from around the world.”

Asked to name the three jewels in the book with the most surprising, intriguing or amusing stories, Post chooses the Logan sapphire, the Napoleon diamond necklace, and the Portuguese diamond (see below). “They are spectacular jewels, and they are connected to very different but equally fascinating people. But know that the next time, I will answer this question differently.”

The big donations

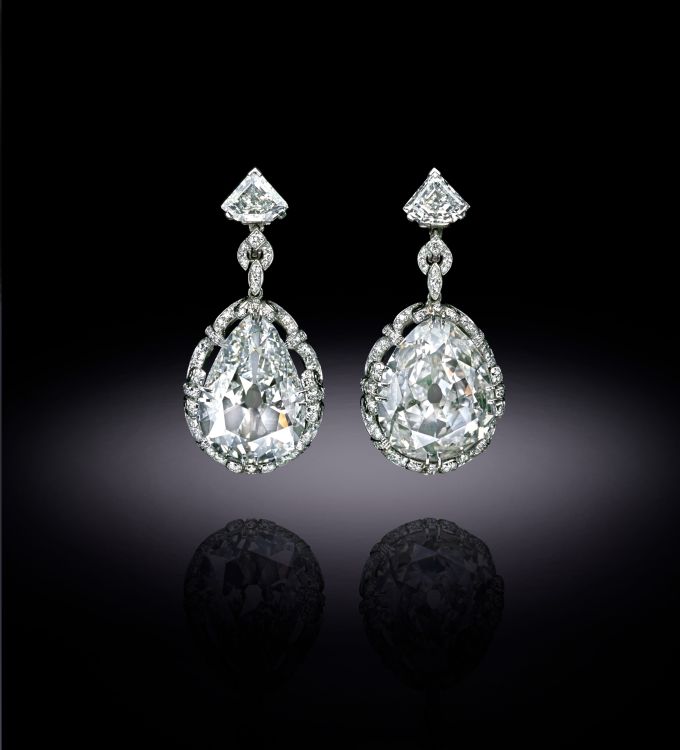

When Harry Winston gifted the Hope Diamond to the collection in 1958, it was a fundamental acquisition for the museum. “It is difficult to overstate the importance of [that] gift,” Post says. “It made us a destination to see this great diamond and established the beginning of our modern National Gem Collection. If the Hope was the trigger, it was a series of major gifts from [heiress] Marjorie Merriweather Post in the 1960s that secured our reputation as a major gem collection. Her gifts included the Marie Antoinette earrings, Napoleon diamond necklace, and Blue Heart diamond.”

These are far from the only treasures the museum has received, however. “In the past 20 years, our most important gift was probably the Carmen Lúcia ruby. Our collection was lacking a world-class Burmese ruby, and this gift more than made up for that deficit. At over 23 carats, it is perhaps the finest large gem ruby on exhibit anywhere and is one of just a few of that size and quality ever mined. The ruby was a gift from Subway [restaurant] cofounder Peter Buck in memory of his wife — so it also represents a touching love story.”

In addition, the curator points to “several major new gifts that already have become visitor favorites — e.g., the Dom Pedro aquamarine, the Whitney topaz, and the Kimberley diamond. There are even some very recent gifts, including two historic American diamonds and a stunning green garnet.”

Of course, searching for the next great gem to add to the collection is always on the agenda, Post says. “Probably at the top of our wish list now is a world-class Kashmir sapphire, something over 10 carats — preferably with a good story.”

Piquing curiosity

In sharing the backgrounds of the stones in Unearthed, Post aims to “introduce gems as more than just valuable and pretty ‘baubles.’ Rather, each gem is a portal into a rich and sometimes fascinating story. Each started as a mineral crystal that formed in the earth, and in many ways, that is the miracle behind a gem. Each gem is unique, and if you have ever seen them being mined, you realize that none are found easily.” In the ensuing stages of the journey, “a skilled cutter imparts a creative artistry to the stone, and in some cases, other artists and craftspeople design for it a fabulous piece of jewelry.” Then there are the people who possessed the jewels, whether they were rich and powerful or just ordinary.

Post hopes “that after reading the book, whenever someone looks at a gem, after admiring its beauty, [they] will ponder: But what is its story?”

THE LOGAN SAPPHIRE

Mined in Sri Lanka, this 422.98-carat gem is one of the world’s largest faceted blue sapphires. Set in a brooch surrounded by 20 diamonds, it was a surprise gift to socialite Rebecca “Polly” Pollard Guggenheim from her husband, Colonel M. Robert Guggenheim, in 1952. While Polly Guggenheim was an active patron of the arts and a philanthropist, her husband was known for his amorous indiscretions. He died in 1959 after dining with his mistress in a Georgetown restaurant while his wife was ill in the hospital. Guggenheim — who remarried in 1962 to John Logan — agreed in December 1960 to donate her sapphire to the Smithsonian Institution, in part because it reminded her of her unfaithful husband. Under the agreement, she was allowed to keep it in her possession until she formally presented it to the museum in 1971.

THE NAPOLEON DIAMOND NECKLACE

Napoleon I gave a gold and silver necklace of 234 diamonds to his wife, Empress Marie Louise, in 1811 after she gave birth to his son and heir. Passed down through Marie Louise’s Habsburg family, the piece took a strange detour in 1929, when Archduchess Maria Theresa attempted to sell it in America by consigning it to a “Colonel” Townsend and his wife “Princess” Baronti. They in turn enlisted Archduke Leopold of Habsburg, Maria Theresa’s grandnephew. Unfortunately, the pair turned out to be swindlers. Although their attempt was foiled, they were able to skip town, leaving the Austrian archduke to face charges of grand larceny. He was ultimately acquitted, and the necklace returned to the Habsburg family in 1932. In 1948, it sold to gem dealer Paul L. Weiller. Jeweler Harry Winston acquired the necklace in 1960, selling it to heiress Marjorie Merriweather Post in 1962. She donated it to the Smithsonian later that year.

THE PORTUGUESE DIAMOND

The octagonal, 127.01-carat Portuguese diamond was a featured attraction from 1951 to 1957 in Harry Winston’s Court of Jewels exhibition as it toured America. Although touted as a mid-18th-century find from Brazil that became part of Portugal’s crown jewels — hence its name — it was actually discovered in 1910 at the Premier mine near Kimberley, South Africa. New York jeweler Black, Starr & Frost bought the stone shortly afterward, and it was set in a choker-style platinum necklace with three rows of 383 small diamonds. It sold to former Ziegfeld Follies girl and jewelry lover Peggy Hopkins Joyce, whose reputation for marrying — and divorcing — wealthy husbands was the inspiration for the heroine in Anita Loos’s novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, according to Unearthed. In October 1951, she sold the gem to Harry Winston, who traded it to the Smithsonian in 1963 for a parcel of small faceted diamonds.

Main image: The 45.52-carat Hope Diamond is set in the platinum necklace designed by Cartier Inc. in 1911 when it was sold to Evalyn Walsh McLean. It is surrounded by sixteen approximately 1-carat brilliant-cut white diamonds and suspended from a chain with forty-six white diamonds. Photo: Penland, Smithsonian Institution, enhanced by SquareMoose Inc.

1 Comment

I went over this website and I believe you have a lot of wonderful information, saved to favorites (:.