The iconic house where Juliette Moutard and Suzanne Belperron, among other gifted women artists, started their promising careers was, paradoxically, named after a man: René Boivin. In this episode of the Jewelry Connoisseur podcast, Rapaport’s Editor in Chief, Sonia Esther Soltani, discusses the fascinating story of the French maison with Vanessa Cron.

An independent historian, consultant and lecturer, Geneva-based Cron is also the creator of the Jewels and the Gang Instagram account. She works as a teacher at HEAD, the Geneva University of Art and Design, and oversees jewelry courses at Christie’s Education, having worked for the auction house as a jewelry archivist and senior cataloguer.

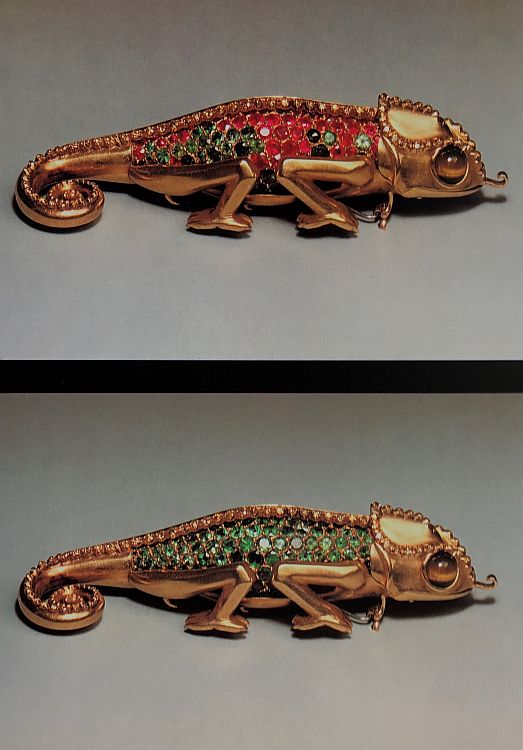

René Boivin designs were generally unsigned, yet Cron characterizes them as particularly sensual and recognizable, with their distinct features making them stand out among the jewels created in the first half of the 20th century. “The Boivin jewels have not really been following the main characteristics of this time period,” notes Cron.

Founded in 1890, Boivin was a remarkable house, even though it never had a store, in contrast with many other traditional houses. “The more you see [Boivin pieces], the more you understand and recognize them. It’s really a question of feeling;” says Cron. Boivin is about more than the jewelry, she adds.

René Boivin was born in 1864 and died in 1917, during World War I. A master jeweler and engraver, he was inspired by nature and never followed fashion. He worked mainly for a range of traditional houses, selling them his creations. “But he already had something of a twist into his jewels because he was inspired by antique jewels and ancient jewels like Etruscan, Egyptian,” Cron points out. She also identifies the influence of the Art Nouveau movement on these sculptural, bold pieces, which are still being sold in auctions and shown in museums.

After Boivin’s death, his wife, Jeanne, developed his style further, never changing the maison’s name. “She went with shapes, she went with colors, she went with different materials because she was not a traditional jeweler,” Cron says. “She was not designing — she was not making them at the bench — but she still had a very strong idea of what a jewel should look like and it had to be very different from traditional jewelry, and that’s when the style of Boivin as we know it now started.”

Although the Boivin house hasn’t produced any new work for about a quarter of a century, jewelry connoisseurs are unlikely to forget the Starfish brooch designed by Moutard, which is now on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). Moutard influenced the maison tremendously during her 40-year tenure as a designer for Boivin. Jewelry lovers remember this timeless masterpiece for its bold size and volume, the flexibility and touch while holding it, and of course, the sheer creativity, Cron observes.

To listen to the Jewelry Connoisseur Podcast, click below.

Main image: René Boivin starfish brooches (photo: Vanessa Cron); Vanessa Cron.

Comments are closed.